“Catching a moment in someone’s life; black and white photographs going back to any era, they haunt you”. It’s something a photographer might say, or a gallery goer, but it’s extra special hearing it from the subject of just such a photo. I’m mid-interview with Patrick, or “Ped” as he’s known, who I’ve tracked down after decades of being obsessed with a photograph he features in.

Ped has never been interviewed before; except, as it turns out, by the police. He’s the taller of the two lads in this photograph taken in 1972 by Daniel Meadows and entitled ‘Hell’s Angels’. Both lads are staring at us like they don’t care what we think, both dressed in denim jackets and jeans, and zip up boots just over ankle height. Under his jacket, Ped is wearing a Hell’s Angels t-shirt, a ripped shirt, and a jumper. The other lad is wearing two belts and carrying a small package under his arm.

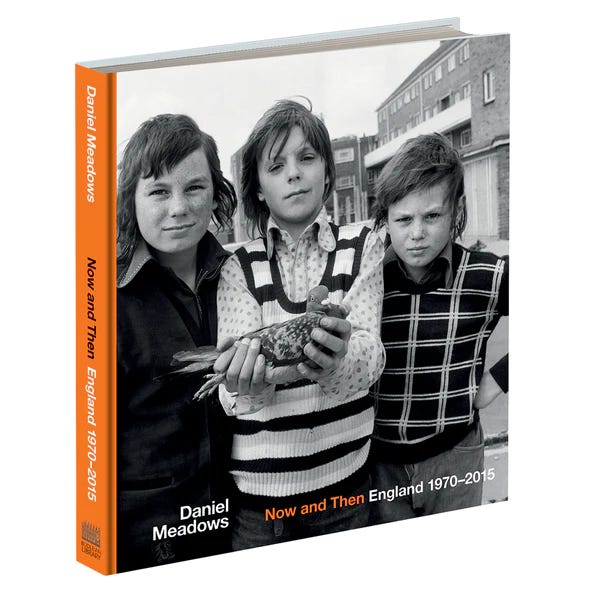

I’d seen the photo online, in exhibitions, and, most recently, in Now and Then: England 1970-2015 which collects some of the photographer’s finest work. ‘Hell’s Angels’ is a photograph without a story. Daniel Meadows has published names, notes, audio - and recently video material - relating to some of his portraits, but no background details about this photo.

I have questions. Are they brothers? Were Hell’s Angels a thing in 1972 Moss Side, a poor working-class often demonised district of Manchester an area known for its Afro Caribbean community? What’s in the package? And what’s their subsequent story?

I guessed they were maybe 17, 18 and into Black Sabbath. My very elderly father judged them to be “thieves”. One of my friends fixated on their strong look, deciding they could just as easily have been a couple of fans of the late 1980s American proto-grunge band Mudhoney. I reckoned LSD might top a list of their favourite drugs.

Earlier this Summer, I walked up a garden path towards an open door of a house in a small town in the Calder Valley, deep in the Yorkshire Pennines, and received the warmest of greetings from Ped. Then we went back to 1972, and Ped laid bare his life. A Moss Side story of deadening factory jobs, split families, early deaths, prison, music, and a fierce loyalty to the neighbourhood he was born and brought up in.

Ped remembers some very established families in Moss Side, but mostly a transient population in lodging houses, or cheaply rented homes. In 1972 the area was experiencing the so-called ‘slum clearances’; streets of old Victorian terraced housing being demolished and communities dispersed (just as they had been in the neighbouring district of Hulme a few years earlier).

Daniel Meadows was twenty years old, a student of photography at Manchester Polytechnic. He was inspired by a democratic impulse and influenced by Bruce Davidson’s photographs of residents of East 100th Street in Harlem, the work of Bill Brandt, and Irving Penn’s ‘Worlds in a Small World project’. “I wanted to make a record of the people who lived there before they dispersed,” Daniel Meadows later explained.

Meadows took the former Charles’s Salon barber shop at 79b Greame St, just around the corner from where he was living on Yarburgh Street, and began offering free portrait sessions, usually on Saturdays. He featured locals and passers-by including female football fans on their way to see Manchester City play at Maine Rd - wearing flares, silk scarves, and a sparkle in their eyes - and a young boy called Neville Davis, pictured with his sister Antoinette.

Ped didn’t book-in or get dressed up or down; “It was spontaneous, completely and utterly, those were the clothes I was wearing walking the streets in 1972. The other fella’s called Eric. I didn’t know him well, but he was a Moss Sider. I remember going to visit his sister and brother-in-law and their kids on the edge of Hulme near the old Dunlop factory a couple of times. He was a sweet lad. It was just a period of months when I knew him on and off”.

Ped looks older than Eric, but apparently they were the same age; “I’m not a tall person but I was a head taller than a lot of people. Generally people were shorter; we didn’t have the diets. We were born in the 50s, mainly, and some in the 40s, you didn’t have the diet”.

I reminded Ped that Daniel Meadows came from a very much more prosperous background; “I love him for that,” he replies. “When he talks about the things he does. He had a genuine love for the world”.

Among his many projects after Moss Side, he went on a journey in a old double-decker bus, photographing almost a thousand people in over twenty towns and cities. Meadows collaborated with Martin Parr in 1973 (who was a contemporary and friend of his at Manchester Polytechnic); the two photographed families at home in June Street, Salford. Meadows’s evocative and invaluable photographic record of urban working class society in Britain is now housed in the Bodleian Library. An exhibition of the bus journey photos is currently featuring at the Centre for British Photography.

I begin to explain to Ped how I’ve been guessing about him and Eric, given that the only information we have ever had is the year, the place, and a title…

He interrupts “Which is wrong. I would have called myself a ‘greaser’. We had pretensions that when we were older we might have the prospect of a place in a Hell’s Angels chapter, but really that t-shirt was a 17 year old’s romantic idea, a wish”.

We hunch over the photo. He’s wearing a shirt with the sleeves ripped off it, he points out, as well as the Hell’s Angels t-shirt that Ped recalls was green. “It was a mate of mine’s and he said I could borrow it and he never got it back”.

There’s a reason the jeans have a shine on them; “We took apart old motorbikes, to make “bitsers”, the best bits you could get off other bikes; so that’s oil mainly. The jacket is denim too, looks like a Levi; but I remember it being stiff with oil and grime”.

Eric has two belts, I point out. “Yes, one keeping his trousers up and one for potentially hitting people with. It was a weapon that wasn’t used as a weapon, if you like”.

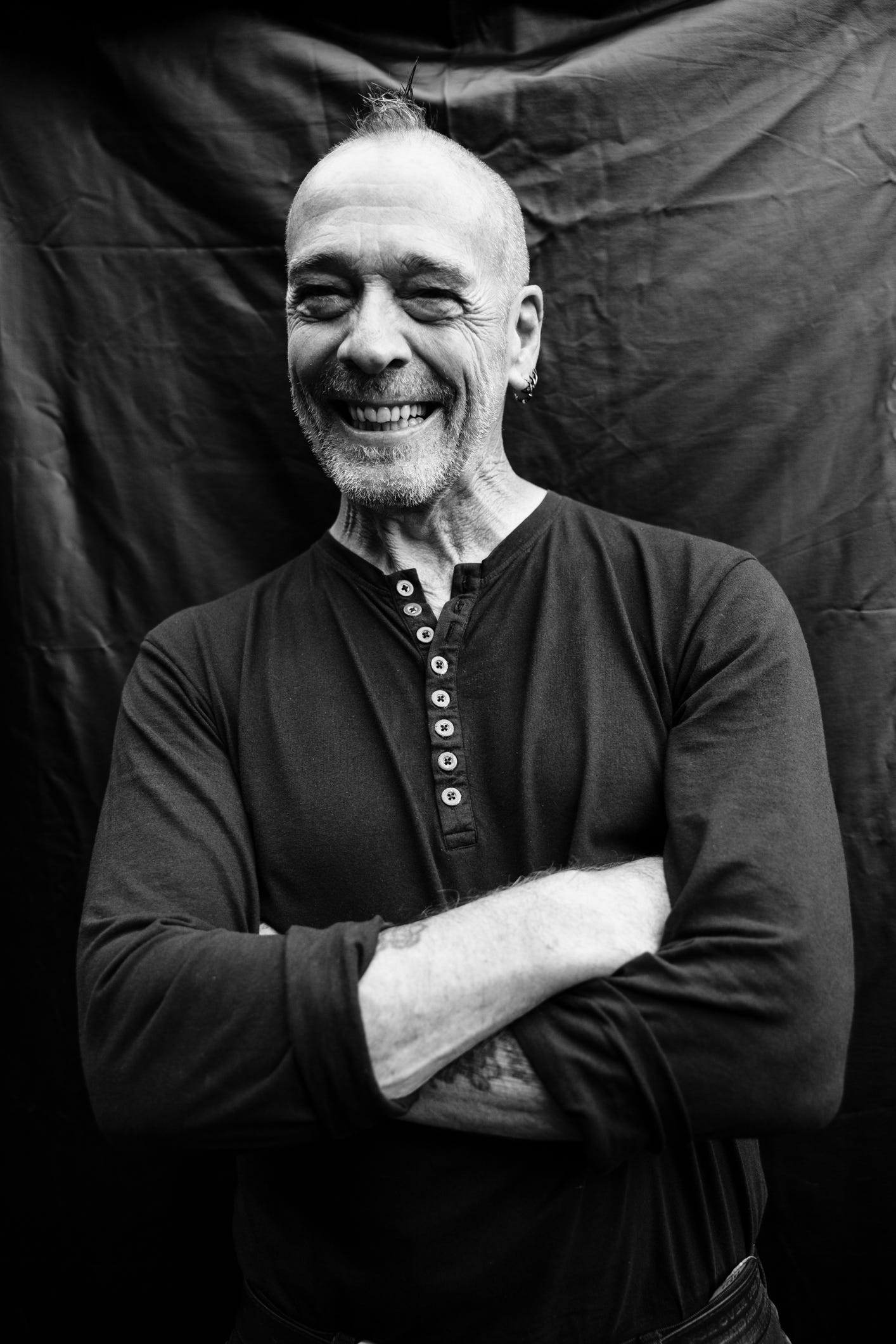

Ped in his late Sixties is softly spoken, still dressed in all black, and healthy-looking; like someone who might have bought the Cure’s first album and now enjoys walking the hills and working in his garden (when I ask him if he bought the Cure’s first album, he says he didn’t). There’s a brightness about him, but he’s nervous about his answers. “Is this OK?” he says to me more than twice.

He seldom saw his father; “I saw him a couple of times when I was a child. He couldn’t stay still. He was looking for work in the 1950s, travelling round Britain. I don’t think he could ever settle down once he’d left the farm in Ireland”. His father was ill with cancer in 1983, at first unbeknownst to Ped; a cousin tracked Ped down, told him, but - before he could act on the information - his father had died.

Ped’s mother was from Liverpool. “There was Irish in her family too,” he says. “And Jewish as well”. After his mother and the young Ped were forced out during the Hulme clearances in 1964 they had a four or five years wait for a flat, before one was offered to them just across Brook’s Bar, on the 13th floor of a high rise. He was living there, on the 13th floor of Eagle Court, when Meadows took his photograph.

Ped and his friends would scavenge the demolished houses, seeking out lead and copper to sell on; “They’d turf people out, and we’d make our move. We made quite a lot of dosh out of it”.

Ped was living on his wits, resistant to the life most clearly laid out before him; as what he calls “factory fodder”. He left his Secondary Modern school with an O Level; “I ended-up in factories doing the things you do in factories,” he remembers. “I had an apprenticeship in a factory in Ancoats embossing leather, metal. I got the sack for being scruffy. I didn’t want to work. I wasn’t lazy, I just wasn’t interested. The pressures on kids now, it’s crucifying. It‘s all this get a job, get a house. The Seventies to me was pure freedom”.

Selling the lead and copper was illegal, but he didn’t care; “It brought in money. And we liked our microdots, and our dope, and to have a drink. And that’s what funded us”.

Some established residents kept their houses and yards clean and tidy, hanging on to respectability until the bulldozers arrived. But in the streets earmarked for demolition, several empty houses became squats. The area had also always been known for shebeens, illicit parties in private houses, usually with reggae as a soundtrack.

A handful of pubs and two late night clubs in Moss Side stayed open through and beyond the clearances; including two adjoining black music venues on Princess Rd, the Nile and the Reno. But shopping was killed off the area’s two busy shopping streets Princess Rd and Alexandra Rd. The sense of community was decimated. In an interview included in Now and Then: England 1970-2015, Neville Davis recalls “The slum clearance killed Moss Side”.

Ped agrees, but believes the Moss Side clearances weren’t an accidental planning mistake, but something that was strategic; “I’m not into conspiracy theories but I do think that there was an element of purpose, an experiment in social engineering. The sheer working classness of the area, the black community, the Irish; they broke us up. We were a strong community. No-one had anything and they treated each other with a certain respect. We were in it together.”

I tell Ped I had him marked down as a Black Sabbath fan. “I can’t not love Sabbath,” he replies. “I went to a few gigs, like Hawkwind and Sabbath in the early 70s, but the Nile was more important to me than any rock music. Moss Side was where I felt my culture was. I spent a lot of time in shebeens and at the Nile club, right through the 70s, from bluebeat right through to the heavy dub”.

His lifestyle choice was rare among greasers; “There were only a handful of us really, many of them wouldn’t touch reggae with a bargepole, but me and a couple of mates adored it”.

When I ask him when he left home, Ped coughs, hesitates. He’s been a little slow revealing a big piece of the jigsaw; “I was on remand at the time that the picture was taken” he says.

With a group of others, he had been involved in a robbery. “It was something or nothing,” he says, but admits things escalated when the police raided the house where the suspects were living and found a firearm. He was arrested alongside four others; “The two oldest got seven years, the two in their twenties got two years, and because I was just eighteen I got borstal. The older guys were on various other charges, including affray which is a serious charge”.

Ped stayed a month at Strangeways, then was sent to borstal at the former RAF base in Pollington; “I learned to play rugby there. We were playing police teams. We were playing men! It was horrible”.

At the time of the photograph, the clearance of Moss Side had barely begun. By the time he came out of borstal there was almost no-one left in that part of Moss Side. Greame St, Yarburgh St, all the streets had been flattened; the people Daniel Meadows had photographed had been sacrificed and scattered.

Ped moved from Moss Side to Gorton after marrying in 1974. Gorton was where his wife was from; “I didn’t like Gorton, I thought it was an awful fucking place. I think I was more confused than anything, maybe I was traumatised by my incarceration without realising it at the time. I felt washed-up on the shore somewhere”.

He describes that part of his life as “really hard”. His mother died in 1977, just short of fifty. He and his wife had three children in a short period but by 1979 the marriage was over; “I blame myself rather than her. My wife was from a massive family and she felt alive and whole surrounded by them, whereas I felt crushed. I felt like it was going to kill me.”

He was able to see the kids, up to a point, then things became so difficult. There were years when he had no contact. I ask after them now; “Two of them are dead,” Ped tells me. “Shane died in 2011, my daughter Rebecca died last year, and the third one is living in Manchester”.

Neither of us knowing what to say next, instead we both look down at the photo in the book; “There’s something very poignant looking at that lad and thinking how it will all unfold,” I say, breaking the silence.

At the end of the 1970s, Ped went back to Moss Side, then hitched to London and lived for a time with some bikers in a Hackney squat before relocating to the Calder Valley, first in Walsden. The Valley has attracted many emigres from Manchester giving their lives a rural reset. He tells me he’s never learned to drive, owned a passport, or had a bank account; laughing, he calls this “a political, but futile, statement”.

Ped gradually fell into tidying peoples’ gardens, and then picking up knowledge about plants, teaching himself as he went a long, learning how to build and repair dry-stone walls. I compliment him on the glorious green garden out front; “Outdoors is my life, walking, gardening, growing things”. He’s been here with his partner Claire for eight years, which he says is “ridiculous”. Eight years in the same place; it seems like he’d expected to be restless forever.

I’m still wondering what Eric’s carrying under his arm in that package. “I honestly don’t know”, says Ped. “We were on our way over to Claremont Rd I believe, where he was going to deliver it. It might have been something his mum had given him to deliver to his auntie”.

“Part of me still wishes it’s some nefarious activity”, I admit.

He shakes his head; “I don’t know but I suspect you’d be disappointed if you found out”.

Ped has no idea where Eric is or what happened to him, or if he is alive; “No, and I never knew his surname - so sadly he’s gone from my life”. We look one last time at the photo; “Well”, says Ped, “In a way we’ll always be bound together”.

NOTES

Thanks to Ped for his hospitality and honesty.

Thanks to Daniel Meadows for his enthusiastic response to my project to find out more about the photograph.

And thanks also to Debbie Ellis at debbieellisphotography.com for the photos of Ped in 2023.

My grandparents lived in a ‘slum’ in Hulme and got shipped out to Denton to spend a few years in a tower block with total strangers. They managed to get back to south Manchester eventually and ended their days in a ‘circle’ on the enormous Fallowfield council estate. I understand why the ‘slums’ had to be cleared but it seemed to be done in such a random and haphazard manner. For people who’d lived in little back to backs for decades to be suddenly stuck in flats a hundred feet off the ground with no neighbours from the old street was disorienting and alienating.

I would have been 17 in ‘72 when that picture was taken. We lived in Elmswood Avenue in Moss Side behind the bus depot. My mum always insisted it was Fallowfield but I was proud to say I was from Moss Side - it made me sound tougher - and anyway Parkside Road was the border wasn’t it? The argument continues to this day and she’s nearly ninety.

Going back a couple of years to ‘70 we didn’t wear biker gear like Ped we were a kind of sub skinhead genre. Tonics and Ben Shermans, but loafers not DMs. A barathea blazer in navy blue with a Lancashire rose on the pocket. A crombie overcoat. The haircut was like a grown out crop, still is, albeit silver now. The music was bluebeat and Motown. We went to the Russell Club and danced in lines, boys one side girls opposite, shuffling left and right, little effort required. Smooth. My girlfriend, a fan of The Osmonds and the Bay City Rollers, had a tartan scarf tied round the waist of her suede mini skirt. And by the time Daniel Meadows took that shot of Ped and Eric I’d discovered prog rock, quit school, started work and grown my hair to shoulder lengt

Great article and a poignant read. Too many communities have been ripped apart for the sake of social engineering and diluting a politically perceived threat. Congratulations on your persistence and best of luck to Ped for the future.