On July 18th 1980, Closer was released. This is a track-by-track celebration, forty-five years on from the release of the iconic album. I’ve got a million things to say and celebrate about the album, the background to the recording, the sound of the songs and meaning of the lyrics.

Joy Division had recorded their debut album, Unknown Pleasures with producer Martin Hannett at Strawberry Studios in Stockport in 1979. For Closer, the Joy Division line-up remained the same as the one that had made the band’s debut - Ian Curtis (lyrics, vocals), Bernard Sumner (guitar, synthesisers), Peter Hook (bass), Stephen Morris (drums).

Tragically, in May 1980, after the recording of Closer - between the 18th and 30th March - and the release of the record on July 18th, Ian Curtis took his own life.

For Closer, Hannett was again in attendance, but the recording took place at Pink Floyd’s Britannia Row studio in Islington, London.

Joy Division drummer Stephen Morris recalls that Britannia Row had “a certain brutalist air”, but the equipment was state of the art and the group enjoyed the fact there was a plate of freshly-made sandwiches awaiting them every day on arrival, and they got free use of Roger Waters’s full-size snooker table.

Both are overwhelmingly unhappy albums, but whereas Unknown Pleasures had a crisp, sometimes punchy sound, Closer is “shadowy and occasionally almost fragile” according to the NME album review written by Charles Shaar Murray the week of the release. The biggest difference is that synthesisers are central to the sound of Closer.

Hannett had always been interested in digital technology, and so had the group. Ian Curtis was a fan of Kraftwerk (spreading the word on them, he gave Hooky a copy of the Autobahn album). Bernard has spoken of Ian also being into the work of pioneering electronic music producer Giorgio Moroder.

Bernard was enthusiastic enough to build Joy Division’s first synthesiser from a kit – a Transcendent 2000. Stephen spent as much time in electronic shops, as record shops. He recalls being there “eyeing up every gleaming new device on the shelves with the word digital in its name”.

Ian Curtis loved being in a band; it was a world he wanted to be in. He loved writing, invariably carrying with him a carrier bag, often containing a book he was reading - for example, backstage at the the Leigh Festival in August 1979, he had a carrier bag including The Age of Reason by Jean Paul Sartre - and one or two of his own notebooks full of notes, lyrics, ideas. At home at 77 Barton St in Macclesfield, he had what his wife Deborah referred to as “the blue room”, where Ian would disappear into with a packet of Marlboro cigarettes and listen to albums or write or read (it was painted sky blue, and included a blue carpet, and a three-seater Habitat sofa).

Ian had troubles, including a debilitating health problem. Returning North from a show at the Hope & Anchor in London on 27th December 1978, he suffered his first epileptic seizure. He was treated for epilepsy with a cocktail of drugs (Bernard remembers Ian taking five different pills a day); including phenobarbital, a barbiturate. The side effects included mood swings, but the seizures continued; by the early months of 1980 and the recording of Closer they were more violent, and more frequent, even daily. He was advised not to hold baby Natalie, who’d been born in April 1979.

There were complications in his love life. Ian had married Debbie in August 1975. However, Ian had become involved with Annik Honore, a journalist from Brussels who worked at the embassy in London; they’d met at Plan K in Brussels in October 1979. Annik was very much in his life by the first months of 1980.

The band weren’t prone to discussing their respective emotions, and Ian’s relationship with Debbie had become distant. Ian and Annik clearly had a deep intellectual and emotional connection. They exchanged multiple letters, and met when they could. One of his bandmates has told me that Ian and Annik’s relationship was barely physical, probably unconsummated. Bernard calls it “an emotional, intellectual relationship”, telling me “it couldn’t have been further from a rock star and groupie thing”.

Ian’s letters to Annik – handwritten and in capitals - express a yearning for them to be together; they’re honest and confessional, deep and revealing in a way that he wasn’t with anyone else. “I’VE NEVER EXPERIENCED ANYTHING LIKE IT BEFORE, I CAN FEEL YOU NEAR ME ALWAYS AND ALL THE WEIGHTS I CARRY JUST DISAPPEAR” he wrote, in a letter dated 11th March 1980, a week before the recording of the Closer tracks began.

All of us search for such a connection. These are the words of Aglaya Ivanovna Yepanchin in the novel The Idiot by one of Ian’s favourite writers, Fyodor Dostoyevsky; “I want to talk about everything with at least one person as I talk about things with myself”.

While in London recording Closer, the group stayed in a flat with two bedrooms in a modern block off Baker Street. Bernard has a memory of the sleeping arrangements; “I was in the lounge and Martin, Ian and Annik were sleeping in one of the bedrooms, and in the other bedroom Hooky, Rob and Steve”.

Bernard remembers how the occasional presence of Annik at the flat and in the studio could trigger some ribbing from Rob and Hooky particularly. Sometimes this was delivered with “an edge”, he says, although to Hooky - as he once explained it to me - “Northerners are a bunch of piss-taking bastards anyway aren’t we?” When in Annik’s presence, Ian declared himself a vegetarian, which - as his bandmates knew his fondness for kebabs, and his devotion to the pork buns in Manchester’s Chinatown -was met with some surprise.

Bernard recalls that despite tensions in the apartment they were sharing, in the studio there was “a sense of unity”. Getting the music right was something they were all determined about, but also the band were sometimes united in their frustration with Martin. At the end of the session, in fact - and ironically for an album that has become iconic - the group weren’t happy at all with Martin’s production. Stephen Morris told me that he couldn’t listen to Closer for months. He said that moaning about Martin was one of the things all four of the group had in common.

The group already had a number of songs written ready to record for Closer; songs that had been in their live sets for months previously. The later songs tend to feature a more prominent synth sound than earlier ones. A couple of songs were very rough ideas, and were worked-on and finished at the recording session.

Side One, track 1 - ‘Atrocity Exhibition’

‘Atrocity Exhibition’ was one of the earliest written songs included on Closer; first recorded at Pennine Studios for a Piccadilly Radio Session on 4th June 1979, and featuring in most of Joy Division’s set lists throughout the second half of ’79. The Pennine Studio version (produced by Stuart James) features a much more anguished vocal performance from Ian Curtis, very different to the almost glacial style on the Hannett-produced Closer version.

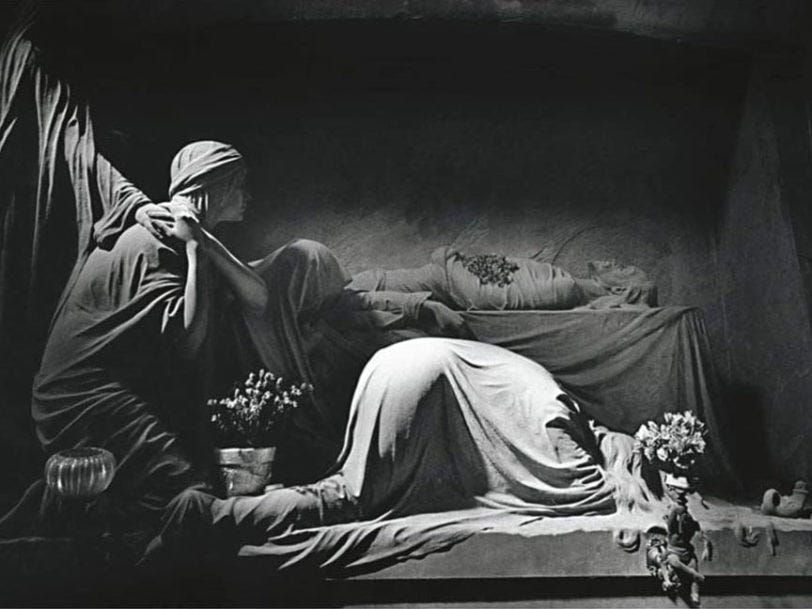

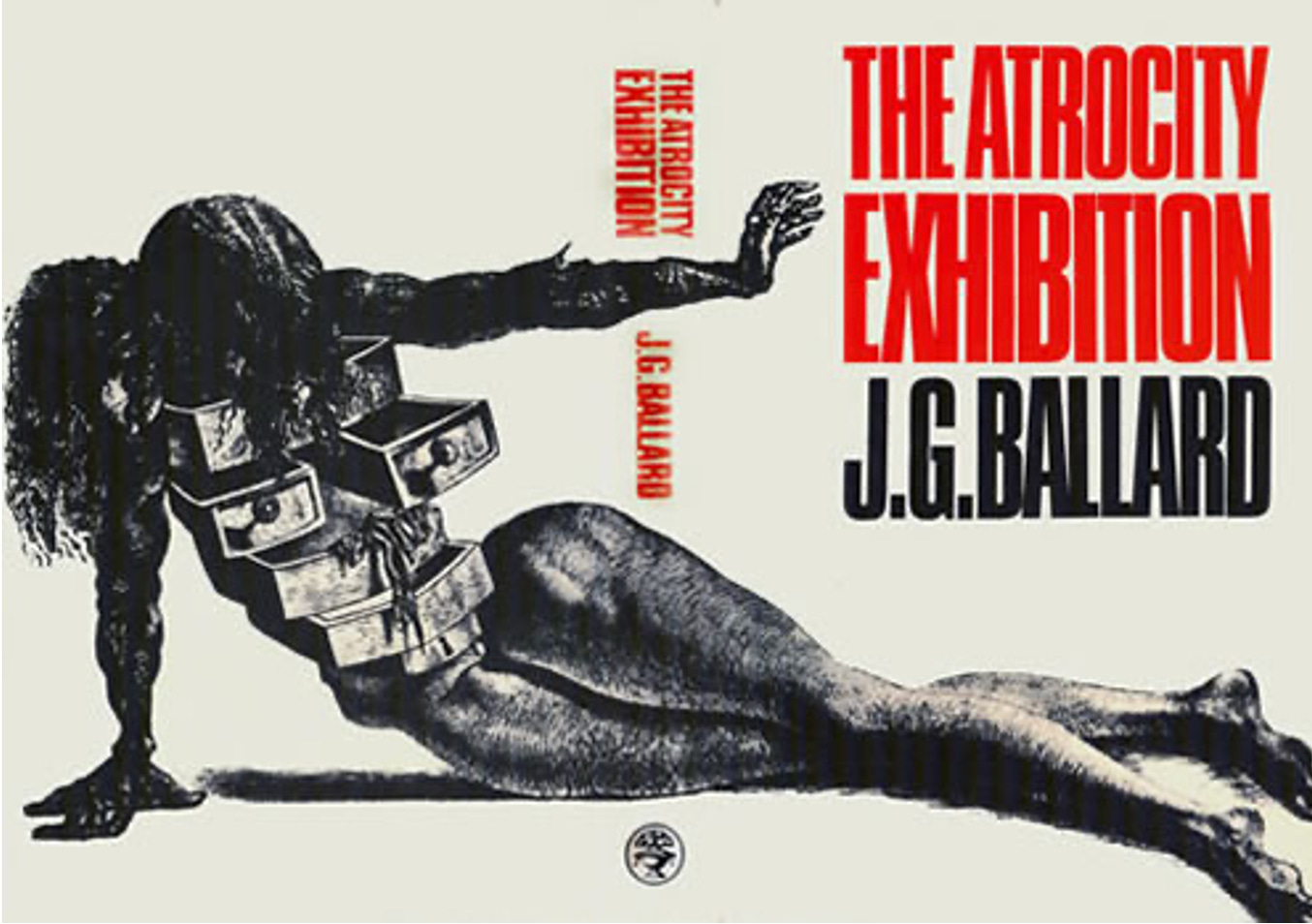

The title references the book The Atrocity Exhibition by JG Ballard; a collection of condensed, connected stories. Stephen once described to me how he and Ian used to browse alternative bookshops in Manchester, like House on the Borderland, one of the few local places to find books by the likes of Burroughs, and Ballard.

When Ian was interviewed by the frontman of Factory band Crispy Ambulance, Alan Hempsall, for the sci-fi magazine Extro on the 8th January 1980, Ian said he'd written the song before he'd read the book: "I just saw this title and thought that it fitted with the ideas of the lyrics"

The track features an almost tribal drum pattern, squawky, squirming noises, and lyrics delivered with a dry, detached, drawl. It’s an appropriate choice to open the album, given the insistent chorus of ‘Atrocity Exhibition’; “This is the way, step inside”. This is the way into the album, but into the Joy Division vision too, their world. Claustrophobic, haunting, disturbed and disturbing.

There’s surely something self-referential, Ian being aware on some level of voyeurism of the suffering artist’s audience, in these words; “For entertainment they watch his body twist”. All connecting to the horrors, mass murder, the “dead wood from jungles and cities on fire”. Not for the only time in the album there’s a sense of battlefields, and allusions maybe to sufferings in a Nazi concentration camp.

There was fascination with Nazi Germany in the Joy Division generation; partly because the horrors were relatively recent yet so seldom discussed, let alone understood. The inhumanity and barbarity were so distant from the school, homework, record shop, football routine. Books, and photos of the camps were passed round. Where did it fit with belief in God? And our so-called “civilisation”?

At the Britannia Row recording of ‘Atrocity Exhibition’, Hooky and Bernard swapped