Passionate but penniless

The creatives in the ‘creative industries’ aren’t getting paid.

When musician Kate Nash announced that she is posting on OnlyFans to raise money to support her work, it highlighted the plight of creatives struggling to make a living.

For people unacquainted with it, OnlyFans is an online platform where women, in particular, post sex photos and videos, which subscribers and others pay to see. Kate says her photos will be racey but not explicit.

Kate Nash has done a lot of gigs recently, including Manchester’s 800 capacity New Century Hall. However, in her announcement she revealed that her decision to raise cash via OnlyFans was precipitated by her live shows actually losing money.

I get the feeling that the public perception is that musicians are millionaires; the airwaves are full of stories about £150 tickets and Oasis and Taylor Swift and Robbie Williams. Truth is, most musicians struggle to make a living, even those with a number one album under their belt (like Kate Nash, who topped the chart with her debut in 2007).

There are thousands of musicians (and DJs, writers, actors, and visual artists) who take a part time or even full-time job to subsidise their earnings, especially early in their career. But with dwindling revenue-making opportunities, established names who’ve been doing OK for twenty years or more are also having to look for ways to keep themselves afloat.

Kate Nash describes sex work as “empowering”. Many may not agree with this; but that’s a discussion for a different time, because right now what I want to do is acknowledge that her announcement brings attention to the financial struggles of artists – of all sorts. Since 2010, for example, there’s been a 40% drop in the median income of visual artists to just £12,500 a year.

It’s clear how broken the music industry is. The staggering thing is that this is at a time when figures show that the music industry contributes £7.6bn Gross Value Added to the UK economy.

It’s broken because the creative people who are at the centre of all this are not getting fairly financially rewarded. I’m going to describe and explain how this is so, but also suggest a few changes to rescue the situation; is there a role for governments, or the Arts Council?

In the music industry, as with so many things in our society, the market isn’t working. Housing, for example; surely it’s unarguable that intervention is required to avoid exploitation by landlords and inadequate quality control for newbuilds, and to boost affordable housing? The water industry likewise. The music industry need intervention from the authorities if it’s going to be fixed.

So who’s making money from music? Spotify collects more than £1bn in revenue in the UK alone. Spotify’s CEO and founder Daniel Ek made $345m in the last year via his salary and cashing-in shares. An artist would have to gain 115 billion streams on his platform to match his earnings. Even a handful of Taylor Swifts put together couldn’t generate that many streams in a year.

At a more realistic level of Spotify activity; on average, artists need four thousand streams of a song to make a tenner. If there are four people in the band that’s £2.50 each. And that’s assuming they have 100% control over the IP, which they probably won’t because third parties will be taking their cut; eg. publishing companies.

In comparison; a tenner is generated from selling just one vinyl album on Bandcamp.

Live Nation’s revenues totalled £25bn worldwide. Live Nation control many of the biggest venues here and abroad; they also own Ticketmaster, the ticketing agency serving these (and other) venues.

As revealed by Kate Nash, live concerts are particularly problematic for artists. Touring acts face steeply rising costs for fuel, overnight accommodation, food, crew. For the vast majority of artists, demand for tickets is vulnerable to higher prices; Kate’s in the £25/£30 bracket. Trying to claw back costs by charging £50, for example, would deter too great a proportion of audience to make a difference to revenues.

Touring for low and mid-range acts never been particularly lucrative, but other revenue streams - vinyl and CD sales notably - kept bands functioning. Income from physical formats like vinyl and CD have plummeted since the late 1990s, of course.

In the 1980s, bands signed to record labels could sometimes count on a chunk of money to underwrite gigs - tour support. Record labels in that old fashioned sense don’t exist like that anymore, which makes comparisons with the 1980s, say, complicated to say the least.

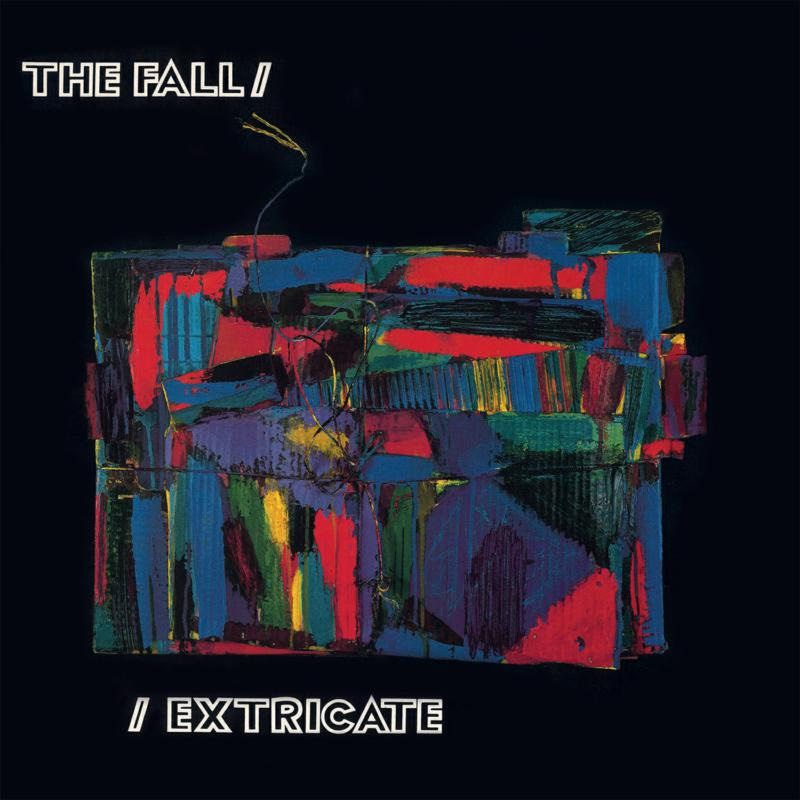

There was plenty wrong with record labels in the 1980s, and I’m sure many artists felt exploited or unloved. Independent labels could be hopeless with money; major labels were often cut-throat and opaque in their financial dealings. But one thing the majors did was to reinvest. I’m taking random names and made-up scenarios, but the point I’d like to make is major labels could make millions out of hit albums by Bon Jovi, Dire Straits, Madonna etc, but a reasonable proportion of that revenue would be invested in signing new acts. And, importantly, acts across different markets. When the Fall were signed to Phonogram in the Extricate era, the major label understood they’d signed a niche act, unlikely to crack the mainstream, but they also knew the likelihood of a full 10/10 album review in NME, the continuing support of the band’s loyal fan base, no expectation of an expensive video, and just enough album sales enough to make the project viable.

In the early 1980s, we were fortunate to have a plethora of cheap spaces in which to operate. Plus, we had a host of non-mainstream record shops, radio DJs, and media outlets that provided potent networks spreading the word.

I mentioned housing a few paragraphs back; it’s relevant to how the cost of living impacts on the artists but also their potential audiences. Kate Nash is part of a generation that has lived through fifteen years of austerity, plus the years of lockdown. Artists and record buyers in their 20s and 30s are faced with historically high rental costs in our cities and many of them are carrying around student debt and working in a low wage economy.

A day or two after the Kate Nash OnlyFans story broke, the Guardian ran a story considering the declining interest among the young for a big night out. I was dreading it turning into old folks reminiscing about countless nights getting hammered and alleging everything was better in their day; thankfully it didn’t turn out to be that really. The journalist, Emine Saner, called me to say a few words and used a few quotes of mine including this; “It’s not that younger generations value culture and music any less, I think that they consume it in a different way and some of their choices are down to the fact they haven’t got the money”.

The world has changed, old models have been swept away by new circumstances; I’m definitely not in favour of a return to derelict warehouses, we’re operating in the here and now, without some of the advantages of previous eras. To make all this more urgent, coming quickly down the tracks is the rise of generative AI. I read in Mixmag recently that a “groundbreaking global study has revealed that music industry professionals could lose nearly a quarter of their income to AI by 2028. The research highlights a projected 24% decline in earnings for music creators and a 21% reduction for audiovisual industry workers”.

If I think back to the early 1980s - not in the spirit of nostalgia but in an attempt to sketch out what advantages my generation had - in addition to cheap spaces for venues, rehearsal rooms, artists’ studios, and so on, students had a free education and the benefits system was far less controlling and draconian (we had several years of the Enterprise Allowance Scheme, a mechanism to avoid signing-on for a year, but still get benefits and housing costs paid). If you think about it, we’d have been inept if we hadn’t taken advantage of the situation to make stuff happen. Likewise, if you look at the economics, it’s no wonder the 1960s were “Swinging” - free education and full employment for the young - and no wonder things are grim now.

Kate says – “People need to find solutions to fund their art”. This struggle is most urgent for creative people from poorer backgrounds, who have no safety net, no family money; they’re faced with huge financial and structural obstacles. I’ve heard it said that already the arts are already considered a career only for those with economic advantages. I don’t think it’s ever too late to open doors for working class kids, and, indeed, there are plenty of organisations and insitutions trying so to do, but to take one example of how piecemeal efforts are not enough; at the level of secondary education, for example, subjects that could give creative kids a start - including music and drama - are falling out of the curriculum and/or fatally underfunded.

Unfortunately the fourteen years of Tory rule were devastating to the arts. Continuing my point about cuts in secondary schools, in 2021 Gavin Williamson - the then Education Secretary - announced funding cuts of 50% for degrees in art and design. Prime Minister Sunak railed against low value “rip off” degrees after former investment banker Philip Augar, produced a report suggesting that courses in the creative arts were providing the worst value for taxpayers’ money and the lowest earning potential for graduates.

The creative industries are very diverse; fashion, film, music, software, publishing, TV, design, advertising. Such activities together are worth £125bn to the UK. You’d have thought an investment banker would have been aware of this. This is more than the fishing industries, aerospace and automative manufacture, and the oil and gas sector combined. The creative industries support around two and half million jobs. In addition to the social and psychological value, there’s demonstrable economic case that providing improved education in creative subjects is good for the economy.

The biggest investors in creative talent are the artists themselves. People will do their best to find solutions to fund their art. Over the last decades I have always marvelled at how dedicated and resourceful artists of all kinds can be. The compulsion to create is hard to erase.

Furthermore, in my years of experience and being out and about, I don’t know any musicians, writers, and artists who want to be millionaires and will complain relentlessly until they are. No; what they want is enough money to make a living and pursue their art. This enriches their lives but also makes a positive cultural, social, and economic contribution to wider society.

I know there’s a lot of research and a lot of initiatives to fix the broken model. Hats off to every creative person who habitually reaches down to pull others up the ladder. I like the charity https://youthmusic.org.uk/ I’ve just discovered and will be investigating https://manifesto.wearecreative.uk/.

It’s arguable, though, that many of the music stars have turned their back on the crisis. As Sean from Drowned in Sound posted on Threads the other day; “The silence from big names (especially very financially secure rich ones), whilst Kate Nash does every media slot going, is baffling. Where is everyone?”

There’s been some great work done championing independent grassroots live music venues, notably by the Music Venues Trust. The idea that there should be a levy on arena and stadium tickets which then gets transferred to grassroots venues is now agreed by the Government. Intervention is occurring.

So many decisions are random, it’s hard to see evidence of a national strategy. Birmingham Council are implementing 50% cuts to regularly-funded arts organisations in the city, and 100% next financial year. But just last week, the Scottish Government announced it was increasing its investment in culture by £42 million (14%).

Anyone who knows me, is already aware that I’m particularly concerned about independent grassroots clubs and venues where the pioneering, weird, and niche stuff happens and acts - including the next-big-things - serve their music apprenticeship. Running costs for such venues are increasing - electricity bills, business rates, pressures from landlords looking to maximise returns.

The thought is that the funds raised by this levy might underwrite costs of running the venues but also contribute in other ways too; ways that will feed into various parts of the grassroots music ‘ecosystem’. Mark Davyd of the Music Venues Trust is, as usual, very good here; talking about exactly what mechanisms for this levy and the distribution of funds are possible in this recent post; https://markdavyd.substack.com/p/the-grassroots-contribution-voluntary

Another helpful intervention would be to amend our complex and expensive trading relationship with the EU which is costing musicians opportunities to make money. It’s been suggested many times that the Government could find reciprocal arrangements with the EU to make the paperwork far simpler for touring acts and others in the cultural sector.

However, it’s not just that the chances to play abroad – and build audiences there - have fallen, but, on top of this, there’s been a huge loss of revenue from merchandise and vinyl sales to Europe. If acts go abroad, they can only take a small amount of merchandise into the EU but otherwise it all has to be declared at customs, and duty paid.

It’s also sending stuff mail order to fans abroad which is hampered by Brexit rules. I know this from my own experience – my publishers had reported steady sales abroad of my short format book series. But, post-Brexit, book orders dropped by a horrendous 95%; books were getting returned by customers or buyers were being asked to pay duties on delivery. Music fans I know in France and Italy have given up ordering vinyl and merch via mail from here.

At Westminster, the Culture, Media and Sport Committee have already called on Spotify to implement “fundamental reform” and called on the Government to ensure that creators are “compensated” appropriately and drawn attention to artificial intelligence concerns. Hopefully this advice will be turned into action by the Government.

So many people in the arts generally work as freelancers. The inadequate measures to support freelancers taken during the Covid pandemic was clear evidence of second-class status. Freelancers need better protections and support. Earlier this year, the Arts Council commissioned a study on workers in the creative and cultural sector in England which declared “The twin impacts of the pandemic and rising cost-of-living have affected the whole sector but are often felt most acutely by freelancers, who are navigating the same issues with less security, and often lower incomes, than their employed counterparts”. A simple first step would be to mandate all organisations and companies to simplify and speed-up payment processes to freelancers.

Young or emerging artists understand that their chosen field isn’t a lucrative one; they are unlikely to share the mindset of an investment banker. I called my memoirs Sonic Youth Slept on My Floor not as some namedrop but to highlight that all cultural advances start small, marginal. The band that Bowie would later describe as “the most important band of the 1980s” slept on my floor after a gig in an Irish club in Hulme. Young or emerging artists understand that the creative life is precarious; they know that there will be early years of toil and perhaps adversity.

In the new reality, however, I would argue that a change in the direction of arts funding is required. It’s something I’ve written about before; that funding from the Arts Council, for example, is too wrapped up in buildings, and cultural institutions. Emine Saner’s Guardian article used another of my quotes; “Great art always starts outside of the cultural institutions; great music starts outside of the major venues”. I’ve long argued that the Arts Council should shift away from institutions and invest directly in people, via grants, perhaps, with a flexible and a relatively informal application process.

I’m a fan of the idea of a Universal Basic Income, but if UBI is going to continue to be resisted, which is sadly likely – it’s not a very Starmer idea – there’s an argument for funds to be directed towards artists who can demonstrate the talent, vision, and ability to take their creativity on from early days to a lifetime’s work. Ideally, a salary from the state. Ask me how much and I’d say between £12,500 and £17,500 a year. For three years. Given that it’s taken six years of work, planning, campaigning, for the idea that grassroots music venues should receive funds from a levy on the big arenas, don’t ask me for details of how the artist-centred funding system would be set up, it would take time to think through;

The salary from the state would of course provide a safety net for creatives struggling to pay bills and/or smooth out the fluctuating revenues of freelancers. But this is the important point - for social and economic reasons supporting human creativity should be regarded as an investment opportunity for society, not a cost.

There are things we can do as individuals, of course; physical product, merchandise, It’s useful even just to spread the word on social media - every like, share, and comment makes a difference.

Usually the comments on my posts are open to paid subscribers only but I’ve opened them to all for this – just in case you have thoughts, ideas, or relevant and useful links you’d like to post or discuss etc.

In the meantime, Season’s Greetings to my fellow writers, freelancers, and music business bods. Let’s hope things will change for the better. Keep the faith. Your work is important. All hail the creatives, and those who love, value, and support them.

Further reading;

A venue that changed a city & the history of music.

I was in Newcastle the other month, for an event at the Biscuit Factory talking about my short format book ‘Adventure Everywhere: Pablo Picasso’s Paris Nightlife’. I had all day beforehand to wander.…

.

Thoughtful and sensible ideas Dave, I like the (French? paris/Berlin?) model of direct UBI to creatives but in this current politicisation of everything it is a mountain to climb. The Arts Council funding grass roots better is slowly happening I feel. I chair a youth music charity called AudioActive in Brighton/Worthing/Crawley etc. We work with a lot of young potential artists and I know that we help provide a positive option for many who might otherwise fall into patterns of violence, drugs or mental health issues - saving local services huge amounts of money in the longer term. So investment into music has so many benefits for communities in addition to filling small venues.

Finally, art is protest. With the attack on creative freedom moving from multi-national (Spotify, Live Nation) to political every moment spent defending creativity helps support our diverse and wonderful nation…

Enshittificaton.

This is the modern world, Dave.

No idea what we do about it, but clearly something does have to be done.

Spotify is villainous, but legal, and we lap it up while bemoaning its awful business model.

Live Nation and TicketMaster are, quite simply, thieves. Legal thievery, but thievery, nonetheless. Yet we buy our tickets from them.

No idea how we change this colossal monopolisation of the music business by just a couple of dozen people and their technological enslavement of millions of us…none at all.

I suspect it is a little too late. Sadly.