Christmas 1959 Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes spent an evening in a Yorkshire pub; sixty-five years on, I went to the same pub, to explore the significance of this episode in Plath’s life.

Plath met Ted Hughes in Cambridge in February 1956, and they’d married in the same year. Late December 1959 Sylvia Plath was six months pregnant. 1959 had been a relatively good year for their respective careers. Hughes had won a $5000 Guggenheim award - a considerable amount in 1959. Plath had been productive, and was clearly entering an important new phase in her evolution of her poetry. In May, she’d proclaimed 1959 as the year of “maturity”.

Plath had enjoyed a burst of creativity after spending time at Yaddo, a writer’s colony in Saratoga Springs, New York; Plath and Ted Hughes were guests there from early September to mid-November 1959. Plath struggled with her mental health on and off during the stay, but with space, time, and in a creative environment, completed several of her most successful poems at Yaddo, including the most excellent ‘Mushrooms’. She’d been pulling together a collection of poems she wanted to submit to the publishers WH Heinemann. It would be her first book, which she’d entitled The Colossus.

The couple had spent 1959 travelling - which Plath described as "a brief nomadic existence before plunging onto the next great phase". Without a permanent base, but now with a baby on the way, in December, they quickly needed to decide where to settle. There had been talk of living in America, but England was now their first choice. London or the countryside? West Yorkshire maybe?

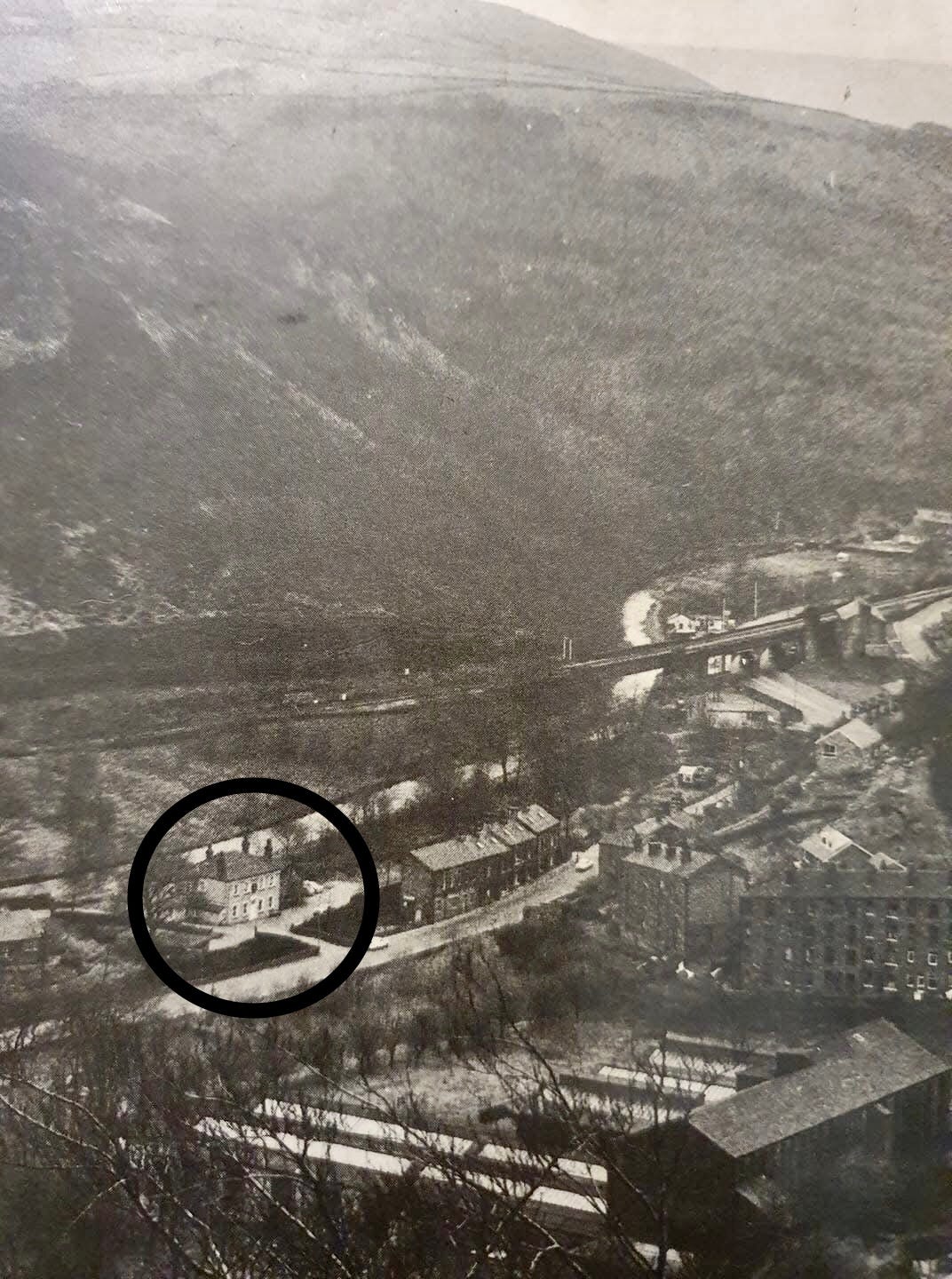

Hughes was born in Mytholmroyd, West Yorkshire in 1930. At the end of the 1950s, his parents - William and Edith - were just a few miles from there, living at the Beacon, a house with uninterrupted views on a rural hilltop on the edge of the village of Heptonstall, which overlooks the town of Hebden Bridge in the Calder Valley below. In 1956 Plath and Hughes had stayed at the Beacon for many months after they’d been married. Their stay is captured in this photo…

Plath writing to her mother in America about that first visit: “Climbing along the ridges of the hills, one has an airplane view of the towns in the valleys; up here it is like sitting on top of the world."

In the 1970s, Hughes would write a little about the towns and villages in the Calder Valley, explaining how the wool trade that had sustained the local economy - and also the non-conformist religious traditions in the locality - had started to collapse in the 1930s. The architecture emerged into “spectacular desolation – a grim sort of beauty”, he said. “Ruin followed swiftly, as the mills began to close, the chapels to empty, and the high farms under the moor-edge, along the spring line, were one by one abandoned”.

In December 1959 the couple returned to the Beacon for a stay until just into New Year; a visit of just over a fortnight. Trawling Plath’s journals and letters it’s possible to bring together details and impressions from that stay. Among the sources, there are plenty of reports in letters sent to her mother, Aurelia Plath.

The year was ending in Yorkshire, but had begun in Wellesley, Boston, at Plath’s family home with her mother Aurelia, and brother Warren (Plath’s father had died in 1940; Sylvia had just turned eight). During the Summer of 1959, Plath and Hughes borrowed Plath's mother's car, a grey 1953 Chevy sedan, and embarked on a drive across the United States, taking in the likes of North Dakota and Wyoming. They then went on to stay at Yaddo, before making the journey back to Britain onboard the SS United States (a five day trip). On 13th December 1959, Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes attended a 'Gala Dinner' on the ship, a day before arriving at Southampton. Plath reported "we had a nice rare steak, lobster newberg, dates & figs". Hughes called the ship “the worst boat on the Atlantic.”

After one night staying in a flat owned by friends in London, the couple travelled up to Heptonstall courtesy of Ted’s Uncle Walt who volunteered to drive them all the way. The train would have taken them over six hours, including a minimum of two changes.

When I researched Plath’s life for my short format book My Second Home: Sylvia Plath in Paris, 1956, I was struck how documents in the Plath archive - letters, journals, stories, poems - were prone to giving different versions of the same episodes in her life. For example, the tone of her letters changes dependent on who the recipients are; this is something we all tend to do. But it was striking how the least reliable accounts of her life are the letters to Aurelia Plath and there are hundreds of them. Sylvia authored a special version of her life in these letters to her mother. It became an arena in which she could maintain an outwardly positive, polished identity, and to reassure Mrs Plath that she was successfully making her way in the world. If she did let negativity or upset into her letters home, she would invariably apologise in a letter a day or two later.

Aurelia had high hopes and expectations for her daughter but they were often different to what Plath envisioned. One issue was Sylvia’s love life and marriage prospects. Aurelia liked to recommend dependable American boys with good jobs. Her daughter spurned this type of boyfriend, appearing to favour untamed or unhinged types. Before she married Hughes, Plath had described him as a “monster” and a “marauder”. It’s a curious thing; she walked into the marriage knowing it was hazardous. For one thing, it chimed with something she’d written years earlier, in her late teens: “I desire the things that will destroy me in the end”.

Sylvia wrote several times to her mother during the fortnight or so at the Beacon, Christmas 1959. One of the features of these letters is how scathing Plath is about Mrs Hughes’s cooking; “Ted’s mother is such an awful cook - heavy indigestible pastries, steamed vegetables, overdone meat,” she says. Edith Hughes’s cuisine was, rooted in a different tradition to Aurelia Plath, and partly a product of a life during wartime and austerity in a land of limited ingredients.

I’m not in a position to argue that actually Mrs Hughes was a great cook, but I suspect that in framing her experiences like this, one of Sylvia’s intentions is to make Aurelia feel valued. Especially when she talks in these terms; “How I miss your kitchen & our family tradition of wonderful food lovingly prepared!”. The Hughes family didn’t even have a Christmas tree.

Sylvia had been with Ted for over three and a half years but that Christmas she repeatedly reports she’s homesick; the home she’s missing is in Boston, with her mother and brother. And, in truth, it’s a home situated ten years earlier, in an idealised past.

Plath’s view of the diet at the Beacon was coloured by her enthusiasm for cooking; in fact, she had less self-doubt about her cooking than any other activity, including poetry. All Christmas, Plath was keen to get involved, to help out, and, in her mind, to improve things; “There’s not even enough flour & sugar here for a cake! Everything very untidy, pots never quite clean, oven bubbling with old fat - a lot of bustle & nothing but burnt offerings”.

Plath enjoyed food. Her preferred way to mark a special occasion, anniversary or birthday was to book a restaurant; when and Ted were in Boston in February 1959, they celebrated three years since their first meeting with fish chowder at Blue Ship Tea Room. Unfortunately, though, they argued over “nothing”, according to Plath, which led to “our usual gloom” in the morning.

Plath aspired to domestic excellence. In such things, she couldn’t help but be a reflection of her generation and her upbringing; wifely duties in middle class Boston families were something to be taken very seriously. Hughes had other theories, including that a kitchen gave her a chance to sideline her anxieties, create, and, in his words, to “escape into cooking”.

Aspirations to domestic excellence are nearly always destined to become a kind of self-torture. Especially as Plath was full of other urges which conflicted with domesticity, including a desire to write. She also knew there were unconventional experiences that could be chased, but this often remained theoretical in her life; we all know the Beat poets never would have become a byword for bohemianism if they’d had a compulsion to tidy a kitchen or treasured the idea of parenthood.

In a letter to Mrs Plath in the early months of Sylvia and Ted setting up home for the first time, Sylvia asked her mother to send her favourite recipe book over to England; The Joy of Cooking, by Irma Rombauer. Plath’s original, and annotated copy of The Joy of Cooking was auctioned by Bonhams in 2018. On one page she notes how Ted is a big fan of her veal dish (“Ted likes this”). The book sold for £4,375.

Plath liked to try a few culinary experiments; earlier in 1959 she cooked brains. “I made them with a pungent wine sauce and they were ghastly”, she writes in her diary. “Even Ted couldn’t eat all of them”. It turned out he didn’t like Plath’s brains.

Plath was very proud of her lemon meringue pie, though. And in the last few days of her stay at the Beacon she managed to increase her time in the kitchen, serving up various dishes to the Hughes family, including meatloaf, oatmeal cookies, and German apple cake. Cooking and eating these dishes “makes me feel a little less homesick”, she explained to her mother. She hints, though, that the meatloaf, in particular, didn’t get the appreciation she thought it merited. Ted as you might expect was not a cook, but he often offered to make coffee.

The kitchen at the Beacon had become disputed territory. After an initial warmth, tensions surfaced between Plath and Olwyn Hughes (Ted’s sister). Plath was delighted with the expensive gloves from Paris that Olwyn gifted her for Christmas, but the two fell out spectacularly a year on, December 1960.

One evening Hughes and Plath took themselves off to a local pub, The Stubbing Wharf. We have details of their night in the pub in a Hughes poem included in a volume entitled Birthday Letters, published in 1998. Written after her death, and over a period of twenty-five years, the poems in the collection are about his relationship with Plath, many addressed to her, all drawing on personal memories; they’re raw, regretful, thoughtful.

‘Stubbing Wharfe’ (sic) describes Hughes and Plath spending an evening at The Stubbing Wharf pub in Hebden Bridge during the Christmas of 1959, focusing on their conversation about where to live. Plath particularly was unsettled, and needed a plan. Hughes implies - surely in a consciously deluded way - that if they can agree on a house, then the tension and issues between the couple could be resolved.

“All we needed / Was to get a home – anywhere…”

In the end, over the course of that Christmas, they decided to find somewhere to live in London. Early in 1960 they took up the tenancy of a rental flat in Primrose Hill, at 3 Chalcot Square. Flash forwards to Christmas 1962, and the couple had separated; Plath and the couple’s two children, were living at 23 Fitzroy Road. It was there that Plath took her own life in February 1963. Her body was laid to rest up in West Yorkshire, in the graveyard of the church in Heptonstall.

In the visit to The Stubbing Wharf described in the poem, Ted stares into his Guinness, silent, as he often was; not giving off a contented vibe, these silences were “hostile”, as Plath acknowledges and describes them in her journal. For her part, Plath was tired and anxious (as she often was). In the poem we don’t find out what Plath was drinking but Hughes refers to the couple’s discussion about their future life together. He could see good reasons for living in the Calder Valley, even given the surroundings;

“This gloomy memorial of a valley. The fallen-in grave of its history, A gorge of ruined mills and abandoned chapels”

Recently, I took the train from Manchester over to Hebden Bridge; a journey I’ve made many times, for short breaks, day trips, and gigs at the town’s live music venue, the Trades Club. My intention this time around, was to have an evening in The Stubbing Wharf sixty-five years almost exactly to the day since the Plath/Hughes visit.

In the walk across to the other side of the town, I stopped for a drink in Mooch, where there’s always a decent cake to be had and some Plath books to browse; before I moved on, I had a brief leaf through the first full-length biography of Plath, Bitter Fame by Anne Stevenson. I was trudging solo through the dark but glad that it was dry and also happy to be on my idiosyncratic mission.

These are some of the shortest, darkest, days of the year. In the North of England, we get used to the day closing by 4:30pm, but also winter days when the clouds are so heavy it’s hard to tell if the sun has even risen. There’s no light around here, but lots of rain. Plath had only one or two dry days during the Christmas visit, writing to her aunt and uncle that Hepstontall had “no snow for Christmas but about a foot of water”.

I was lucky with the weather, visiting on a dry evening. Unfortunately, The Stubbing Wharf -close to two waterways at the bottom of a narrow valley - is vulnerable to bad weather. It was badly damaged by floods in 2016. Only a few weeks before my visit, Storm Bert, had caused the pub again to be overwhelmed by floodwater, closing The Stubbing Wharf for several days.

Inside the porch, emblazoned on a wall, are the first lines of Hughes’s poem;

“Between the canal and the river We sat in the gummy dark bar. Winter night rain. The black humped bridge and its cobbles Sweating black, under lamps of drizzling yellow”

Walking from the station, I did wonder if I’d gone too far away from the high street shops but I followed Hughes’s description, looking for the black humped bridge, and found it; and, indeed, the pub is squeezed between the Rochdale Canal and the River Calder. There’s a small menu; it’s unlikely that in 1959 this would be a place offering more than maybe sandwiches at lunchtime, and pies in the evening. Pubs like this became “gastro” relatively recently.

Hebden, subsequent to the Plath/Hughes visit, has evolved. Houses and buildings, smoke-blackened by industry, have been sand-blasted clean. The town’s demographic is quirkier than in 1959. As I mention in my book All You Need is Dynamite about the aftermath of the Sixties, fifty years ago the area had become a magnet for squatters and hippies, including the founding of wholefood shops, and places selling “new age” paraphernalia. There’s more about this in a book by Paul Barker called Hebden Bridge: A Sense of Belonging. Various sources, including the BBC website have recently described Hebden as "the lesbian capital of the UK".

In contrast to the “dark bar” of sixty-five years ago, The Stubbing Wharf is well-lit and welcoming. A high-ceilinged, big ground floor room, with the same wooden floor as in 1959 but stripped and polished. Like Plath and Hughes did, I walked in an empty pub. There were Christmas songs playing in the background; the two young staff members greeted me warmly and explained that if I want food I should order from the bar. I was still the only person there at 6.30pm, but within half an hour I was joined by two couples eating, a grandad having a bottled beer with his grown-up grandson, and a solo woman with a quiet little dog.

This evocative photo shows the view from Heptonstall down into the valley in around 1970. A view Hughes once described as “a grim sort of beauty”. I’ve marked the pub.

The Hughes and Plath visit to The Stubbing Wharf was not a good night, for lots of reasons. Generally, is there something about Christmas that can be a problematic season for people who struggle with their mental health? Does the pressure to be positive during Christmas accentuate isolation and/or despair? Does Christmas remind us too vividly of what or who is absent in our life? Does the imminent arrival of the end of the year bring bouts of extra self-questioning and self-doubt? Is it also about being thrown into anxiety-inducing social situations? In the Plath case, there’s also the probable pent-up tension of staying over with Ted’s parents; difficult dynamics in an overcrowded house.

The landscape that had enchanted Plath in the blowy September of the early months of the marriage, in the mid-winter three years later seemed now dark and oppressive. It wasn’t just the weather conditions; she’d lost some of the optimism of mid-1956. Her demeanour in the pub was downcast. In the words of the ‘Stubbing Wharfe’ poem, Plath “sat weeping / Homesick, exhausted, disappointed, pregnant”.

Hughes was aware that the night out seemed like a failure. Despite being loyal to the landscape and the valley, and the community around Hebden, he was struck by the greyness, and claustrophobia;

“....The shut in

Sodden dreariness of the whole valley”

In 1959, invariably a pub could feel like a male space. Plath was probably glad to get out of the house - she’d been enjoying the “roaring fire” at the Beacon, and games of cards with Ted’s cousin - but, in between rain showers, she and Hughes had taken every opportunity to go for walks. If there had been some other place to spend the evening other than a pub she might not have gone to The Stubbing Wharf. To her, pubs were too blokey, and noisy (although she was a fan of a pub in Soho called the York Minster).

Aside from meals in a restaurant, Plath definitely preferred small, domestic, dinner-party type socializing to an evening in a pub, although being so committed to perfection in her life and poetry the build-up to hosting people at home could make her feel tense before the event, and deflated after.

Plath was fragile, vulnerable. In a Birthday Letters poem, ‘Your Paris’, Hughes talks of her “flayed skin”; psychological wounds so close the surface. In some senses, especially after reading the poems in Birthday Letters, it seems Hughes was out of his depth; a no-nonsense Yorkshire man unable to comprehend her struggles. At times it’s clear he misunderstood her mental state, and, sadly, he most certainly greatly exacerbated her battles with her mental health. But he seems to have believed she was the only one bringing disruption to the relationship. This is his point of view, expressed in ‘Stubbing Wharfe’;

“Answering all your problems was the answer To all my problems”

One of the themes in Birthday Letters is Hughes’s perception that the connections between the couple were broken in irreparable ways. In the hindsight afforded to him by writing after Plath’s death, he describes a gulf between them, even from early in their relationship. Different mindsets, different perspectives, never to be reconciled. In ‘Your Paris’ he sees a portent in the name of their honeymoon hotel, the Hôtel Des Deux Continents, implying the gulf between them was as wide as the Atlantic.

There’s a similar moment in ‘ Stubbing Wharfe’ – Hughes describing the contrast of the ruined mills and dark horizons of his home environment, and the “the sparkle of America”. Hughes could imagine a future in the dark hills, close to family. As they mull over the issue of where to settle, he tells her the side valleys are full of the most fantastic houses, going cheap. But he writes: “Where I saw so clearly/ my vision house, you saw only blackness, solid blackness.”

A reminder that Hughes wrote about the evening in The Stubbing Wharf many years after the event; so Hughes would have been aware what was to come, including, a few years after Plath’s death, his purchase of a lovely house in a side valley; Lumb Bank. The poem includes what appears to be a reference to Plath being buried in Heptonstall churchyard. In 1963, after her death, the hilltops above Hebden would become her final resting place

“Up that valley A future home waited for both of us – Two different homes”

I was enjoying my visit, chuckling to myself that this mission to visit the Plath/Hughes pub sixty-five years after them was close to the edge of being properly daft. Conjuring up more absurdity, I decided that my order off the menu should be inspired by Plath. Starter; garlic mushrooms, in honour of the poem she’d written just a few weeks before her visit to The Stubbing Wharf.

Scanning the main courses, I recalled how disappointed she was with fish and chips in Whitby when Hughes and his cousin Vicky had taken her there (I think she was expecting Whitby to be Cape Cod, and instead of wandering round eating out of an old newspaper, they’d find some pastel-painted beachside hideaway serving clam chowder). But during her student years in Cambridge she’d loved a chippy tea. In 1957, Plath had written the draft of a story set in Cambridge, probably drawn from her own experience. The female narrator enjoys a walk to the chip shop in winter, saying to her (male) companion “I’d rather eat fish and chips on a rainy night than anything,” She cradles the bag against her, “feeling the warmth,” she says, “A warm center against the rain”.

So, I ordered the fish and chips. Mushy peas came in a ramekin. Doris Day sang ‘Let it Snow’.

Perhaps aware that she’d been mean about Edith Hughes’s cooking, Plath admitted in a later letter to her mother that she could be over-critical. In that spirit, I’m going to skip a detailed appraisal of the food, and focus on just how bright and friendly the atmosphere in the pub was. I recognised that despite not being much of a fan of Christmas, the evening out at The Stubbing Wharf and the ceaseless Christmas songs in the background didn’t drag me down; quite the opposite. It felt Ok to be me.

I also felt grateful that what I carried through the doors and into The Stubbing Wharf, in contrast to Plath, was a belief that there’s a positive dynamic in the important relationships in my life. But also so grateful to Plath for the inspiration, insight, self-questioning I’ve taken from her writings over the years.

At the end of ‘Stubbing Wharfe’, there’s a twist, the light comes in, there’s some levity. Hughes had given us the impression that the couple had experienced a remorselessly bleak evening in the pub. But we learn that wasn’t quite the case.

In the final lines of the poem, a group of friends enter the pub, laughing and joking with each other. The energy and good spirits of the group distract Plath and Hughes from their anxieties and conflict. The blasts of laughter produce involuntary smiles from the couple;

“I had to smile. You had to smile. The future Seemed to ease out a fraction”

The poem ends here, sharing a communal carefree moment, sending Plath and Hughes back up the hill with a tinge of a positive future. That it’s a little uncharacteristic of Hughes to eke out some optimism makes the fact he does so here worth noting.

In September 1959, Plath had worked on (and then abandoned) a story which she describes as “an essay on the impossibility of perfect happiness”. Even acknowledging that notion doesn’t diminish the power of moments to jolt you towards serenity or joy, or an acceptance of your idiosyncrasies, or a feeling of being embraced by the world. You could be caught unawares; someone singing happily to themselves in another room, your first taste of a perfect fish soup, your friend’s dog making a fuss of you, a small child so happy to be sitting on the front seat of the upper deck of the bus, a rainbow arching across the estuary. We need to collect these moments, feed off them.

The discussion about where to live ended with a resolution to make a go of it in London.

In the first days of the New Year, January 1960, Hughes and Plath left Yorkshire and returned to London to look for somewhere to live. It was stressful and not at all straightforward; on some occasions they’d be dashing across North London in a taxi to an available property, only to find it had been taken. Eventually they found somewhere to live; the flat on Chalcot Square, costing three guineas a week.

With a mix of excitement and trepidation, Plath submitted the manuscript of The Colossus. She found time to buy furnishings for the flat, including kitchen appliances. The book Bitter Fame by Anne Stevenson, includes a rancorous little essay about Plath by a one-time friend of Hughes and Plath, Dido Merwin, which is deeply critical of Plath’s behaviour and attitudes, including questioning her extravagant spending on household items at this time; including a posh cooker, and a large refrigerator. Plath, for her part, took delight in her new kitchen, rubbing the stove and fridge with a cloth, admiring the sparkle.

Her ambition to be the queen of all domestic environs was one thing, but evident throughout the journals and letters is Plath’s ambition - almost desperation - to be published. To be heard. To get the words out of her head and into the world of ideas. On February 5th 1960, Plath received a letter from James Michie of Heinemann thanking her for the bundle of poems and expressing a wish that Heinemann would like to publish them. Ted wrote to his sister; “You can’t imagine how euphoric she is”.

On April 1st 1960, baby Frieda Rebecca Hughes was born at home on Chalcot Sq. Plath remembered later “little funny squiggles of hair plastered over her head, with big dark blue eyes”. Plath’s well-equipped kitchen came in handy just after the delivery; the baby’s first bath was given to her by the midwife in the poet’s biggest Pyrex baking dish.

Further reading

Thanks for the lovely bit of writing, and also the pointer to the Paul Barker book. Hebden Bridge was the subject of my doctorate in the late 1970s when at Manchester Poly, and I recall staying with Paul in London as he was a friend of my supervisor. At the heart of my thesis was the argument that it was Hebden’s failure to modernise in the 1950s and 60s that sowed the seeds of its success in 1980s and beyond as its cohesive Victorian townscape and very, very cheap property attract the first waves of industrial tourism and its colonisation by escapees from Leeds and Manchester.

Loved it Dave! 😃