Jayne Casey is key to many of the best things in Liverpool culture over the last fifty years. The story of her finding her tribe in the mid-1970s - Scouse boys wearing mascara - is wonderful.

A week or so ago, I was asked by someone if I’d consider putting together a collection of my articles, and interviews going back to 1984 including extracts from books. I spent a day or to writing lists of what might be included in such a collection; I’m still considering the idea. But in the meantime, I’m posting this; something I’d definitely love a wider audience to read. It’s from my 2000 book Not Abba about all the stuff the I Love the Seventies type shows never include. The extract features Jayne Casey. The year 1972. And Bowie. And Holly Johnson wearing red tights and Pete Burns in salmon pink trousers.

I like it because it celebrates Jayne, and also Bowie, and gives such a strong sense of music as a source of solace and inspiration. And its power to invigorate the world, to guide us to new emotional and intellectual territories and have fun along the way…

Jayne starred as the startling-looking frontwoman in one of the bands to come out of the punk scene around the club Eric’s, Big in Japan (alongside the likes of Holly Johnson, Ian Broudie, and Bill Drummond), then with Pink Military, who evolved into Pink Industry. In the 1990s she then played a pivotal role at Cream nightclub, and went on to being a prime-mover behind both Liverpool’s European Capital of Culture year and to the creation of the Baltic Triangle. She’s still an inspirer and a doer, having only this year opened District House in New Brighton, off the back of the success of District, the venue she runs with Eric Gooden just off Jamaica St in Liverpool.

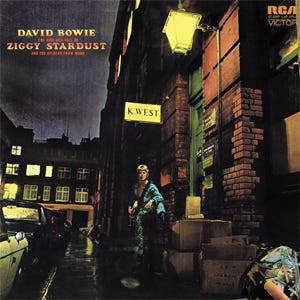

So, this is the extract. Bowie in 1972, and Jayne’s teenage story. Please note - its starts a little abruptly. In the book I’d already spent a few pages talking about Bowie, and Ziggy Stardust.

David Bowie was inspired by Iggy but also fed from the New York of Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground. In New York he found sleaze, deviance and decadence, just as he would later in the decade in Berlin. According to Barney Hoskyns in his history of glam rock, “New York was about drag queens and junkies, small-town freaks transforming themselves into gutter aristocrats as they revolted against America's repressive homophobia."

In England, music fans weren't restricting themselves to the occasional Bowie single, they were buying into his look, even his life. England in the Seventies was the sub-culture capital of the world. Ideas, especially those disseminated through music, moved quickly, and the colour and the controversy surrounding Bowie appealed to kids who celebrated their distance from the Sixties and its music. “Bowie offered noise and glitz and sexual ambiguity as a statement; a boot in the collective sagging denim behind of hippie singer-songwhiners,” according to the sleevenotes of the Rykodisc reissue of Sound & Vision.

Jayne Casey was among those who were drawn to Bowie. At school she says she was a rebel and “really naughty” but used to come top in exams; “Oh God, it used to drive the teachers crazy. They couldn't get it, they couldn't get hold of me but they knew I was really clever. And I left at fourteen and ran away from home.”

She ran away to New Brighton. “It was the only place I'd ever seen with bright lights, away from the house that I lived in with my dad.”

She remembers there were still hippies around, and the first wave of heroin was just hitting Birkenhead. Boats still came in to Liverpool and Jayne came across a group of girls; she stayed with some of the older ones; “They used to shag on the boats and they were all single mums and I used to babysit for them. I just used to move around between their houses. There was another girl who was a single mum who was a heroin addict and I used to look after her kids.”

On a night out Jayne used to go to a club called the Chelsea Reach in New Brighton and dance to T-Rex. She was angry with the ways of the world and could feel it, but had no real means of channelling those feelings. She tried out haircuts and tried to control her physical appearance. Later in the Seventies we would feast our eyes on Farrah Fawcett Majors, and adverts for Harmony Hairspray would be everywhere, so the pressure to be well groomed and easy on the eye increased, but Jayne would continue to prefer what she calls “annoying haircuts”. Into the later years in the decade, she'd cut her hair in spikes, shave it all off again, get it dyed red, and then shaved again.

One day in 1972, the headmistress from her old school knocked on the door. She told Jayne she wanted her to go back to school. “She told me I was the brightest kid she'd ever met and she'd not forgotten me. She'd come to New Brighton. She'd asked round and she'd found me.”

She asked Jayne to go into care. “I agreed and I packed what few things I had and she picked me up and took me to the Social Services office and I sat there until ten o'clock at night until they got me a foster home.”

Despite the opportunity for a new start, she'd get thrown out of one foster home, and then be placed in another the following week, and she seldom settled. She had few possessions, but one was precious: a copy of Simon & Garfunkel's Bridge Over Troubled Water album. Although she could be spikey and confrontational, the album addressed another part of Jayne's personality, embracing her with a warm blanket of melancholia. An LP of acoustic ballads, intimate and well-crafted, Bridge Over Troubled Water was released in 1969, although it wasn't until the 'Bridge Over Troubled Water' single broke into the charts early in 1970 that the LP began selling. By 1975 it had sold more than ten million copies; one of the best-selling albums of all time.

She accepts now that she was a handful for her foster parents. “By that time it was too late really because I'd been brought up by my father and I hadn't been socialised properly. I didn't understand family life, I just didn't understand it at all. I wasn't trying to be difficult, it was just the person I was. I hated the world that I was in, hated the values and just thought it was so hypocritical and shit. I wanted to find boys who wore mascara and leather trousers!”

When she wasn't listening to Simon & Garfunkel, she'd be out painting the town red. The impact of those nights dancing at the Chelsea Reach strengthened as she started hearing things about Andy Warhol, The Velvet Underground and the Factory scene. Thus an instinctive enjoyment of 'Get it On' led her to a new world of exciting ideas: “I'd become aware of Warhol, and I'd heard about the whole Velvets scene, although I don't think I'd heard much Velvets then actually, and I dyed my hair red and got it cut into spikes.”

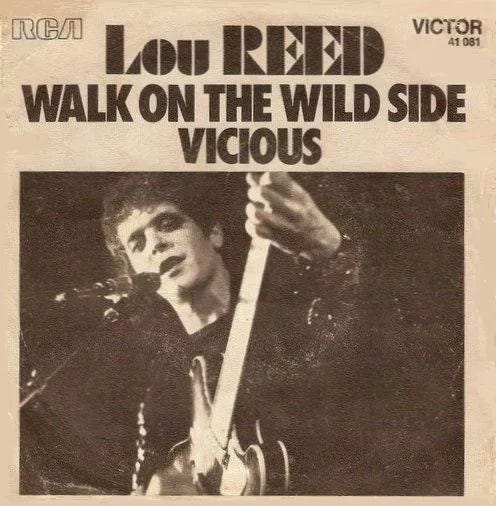

During the summer of 1972, Bowie developed his relationships with the Velvets and Iggy Pop. At a live show at the Festival Hall, Lou Reed was Bowie's special guest, and a week later Bowie hosted a press conference at the Dorchester Hotel and invited Lou Reed and Iggy Pop along. His advocacy of their music gifted them new audiences; both of them played sell-out shows at the King's Cross Cinema during July 1972. Bowie had also taken on the role of producer for Lou Reed's LP Transformer. Iggy Pop, meanwhile, was working on Raw Power. He'd lost his lustre and sold Jim Morrison's clothes, and had been trying to give up heroin but had got stuck using Quaaludes and other tranquillisers. But London energised him.

Although their debts to New York were clear, the backgrounds of some of the era's key English icons couldn't be much further from New York's mean streets. Bowie was born in Brixton and grew up in Bromley in Kent. Roxy Music were also intriguing, in their early days especially; a brilliant band who presented sleek high art concepts in a deviant pop context, but, again, their backgrounds were far from the drug dives of New York. Brian Eno had been Social Secretary at Winchester Art College, and Bryan Ferry, son of a coal miner, had grown up in Washington in County Durham and been taught by Richard Hamilton at Newcastle Art College. In 1970 Ferry had left an r&b band called the Gas Board and formed Roxy Music.

Bowie's Ziggy Stardust persona, plugged into sci-fi fantasy and apocalyptic fear, successfully created a link between the experimental, suffering, fragile rock star - out there all alone - and an astronaut, an alien, a space adventurer. In Bowie's work at the time there also seemed to be some belief in the power of the gifted individual, an übermensch, a saviour; an idea which he developed later, the idea of a 'homo superior', a rider on the storm.

Through 1972, not content with the success of Ziggy Stardust, Bowie also found time to work with Mott the Hoople. Mott had made several LPs under the guidance of Guy Stevens, but their career was floundering and they were on the verge of breaking up. Hearing of their troubles, Bowie offered them a song he'd just written, 'All the Young Dudes'. Mott recorded a new LP during the summer, with Bowie co-producing; 'All the Young Dudes' was the title track and a massive hit in August 1972.

You'd need more than a few songs to define everything there is to be said about the generation emerging during that particular part of the Seventies, marching out from under the shadow of their hippy older brothers and sisters. Some of the rebellion and confusion is there in Alice Cooper's 'Eighteen' (1971), and some of the exhilaration is caught in T-Rex's 'Children of the Revolution', but 'All the Young Dudes' by Mott the Hoople is immense, an anthem for a post-Beatles generation ('We never got it off on that revolution stuff / What a drag'), delivered with all the swagger of a football chant. The dudes are untamed juvenile delinquent wrecks, drinking wine, feeling fine. The record and the band's image were perfect for the times: Mott managed to combine a slightly unnerving take on glam with the emotional hard rock of Led Zeppelin.

At first glance, the era of 'All the Young Dudes' was something of a high water mark for lad culture; lots of drinking, bovver boys stalking city streets, football hooligans causing havoc on Saturday afternoons. But life for lads in 1972 and 1973 wasn't as clear cut as the image suggests; in fact, the young dudes had an identity crisis, as the loosening of authority and a lack of rules was creating self-exploration but also great confusion. There's a character mentioned in 'All the Young Dudes': 'Jimmy looking sweet / Though he dresses like a queen / he can kick like a mule.' Young hooligans would be wearing make-up, skinheads were dancing to black music. In 'Vicious', on the 1973 Transformer album, Lou Reed asks us to hit him with a flower. In 'Walk on the Wild Side', he tells us he was a she.

Bowie spoke to this identity crisis and lads listened; the messages were mixed, but in an age of confusion they rang true. There was an ironic, skin-deep, or showbiz element to a lot of the cross-dressing in the glam era.

At the same time as men were discovering new questions to answer, there was also an increased amount of activity in feminism and the women's movement. 1972 saw the launch of Spare Rib, a magazine established by Rosie Boycott and Marsha Rowe, who had both been around during the very first days of the Virago Press. In the underground press there had been dozens of publications - like Shrew and Harpies Bizarre - but Spare Rib was the first commercial and high-profile feminist-focused magazine in England. But the Spare Rib agenda - campaigning, consciousness-raising and discussing steps forward for radical was only part of the story of 1972; in the same year, out of the consumerist wing of the women's movement, came the first issue of Cosmopolitan.

The developing empowerment of women would take time to filter through nationwide, and Jayne Casey remembers little about the wider debates. A struggling teenager back in Liverpool after her few short months in New Brighton, she was, as ever, relying on her survival instincts. “I was in children's homes and I fucking hated it and it fucking hated me, and I tried to do my A Levels, and I just couldn't stand it, it was just so awful. Oh yeah, this is what happened. They put me into some kind of approved lodging place and I was lodging with a family and the family were really cool actually, lecturers at the University. And I left school much to everyone's disgust and I got a job in a hairdresser's as a receptionist.”

It was 1973, she was seventeen. The hairdresser's was called A Cut Above the Rest, a Manchester-based company with a branch in the centre of Liverpool. She was employed there not to do much, but just to be somebody. “They employed me to sit out front because I was so gorgeous! I was a bit like a kind of Marilyn Monroe lookalike, kind of blonde and tits and gorgeous.”

Back in New Brighton she'd dreamt of meeting boys with mascara. Sitting on reception at Cut Above the Rest, she'd become used to people coming in, hanging around. One day in walked a boy wearing salmon pink trousers and mascara. His name: Pete Burns. He said he wanted a job. 'I think he was fourteen at the time, and there was like no chance.'

But Pete Burns so wanted a job that he returned again and again, and by the end of 1974 he'd started work at Cut Above the Rest. Jayne was soon to meet other lads who were to form a kind of family for her. After Pete Burns came Holly Johnson, and then Paul Rutherford hot on his high heels.

Jayne remembers some of the staff at the hairdresser's were out on the town one night without her, and they came in the next morning and said, “We met this kid last night who was so fantastic and he had red tights on, and his name was Holly.” “I was really pissed off that I hadn't met him. Habitat was next door to us and some time later they all came running in shouting, "The boy Holly's next door in Habitat; come and have a look!" and I did and there he was in Habitat, I saw this creature!”

Jayne had met her boys in mascara in roundabout ways. It had all happened by accident, but there was no other way, says Jayne: 'You didn't meet in clubs because there wasn't a scene.'

If you looked a bit different and you were somewhere in town you eventually found each other. “People would tell you, they'd walk up to you, tell you there's another weirdo down the road! So within a couple of years I'd got a right posse of boys with mascara. I shaved my hair off, and thought, OK, this is it, let's have a laugh!”

Further reading - the joys of an eclectic life

Sticking to your lane

Like everybody else, my life can be complicated and even confusing. I don’t feel very easy to categorise. Sometimes I want to hear ‘The Sound of Silence’ by Simon and Garfunkel, and sometimes I want …

What a character, and a terrific story. I’ve always struggled to connect with a lot of 70s pop culture. Through her story we get a glimpse into a world that in many ways has really shaped where we are today

This is great Dave, she's an inspirational woman. I'd add The Six-Teens and Teenage Rampage by the Sweet to the Glam revolution playlist.